Data consistently indicates that medical issues are the primary driver behind approximately 66.5% of all personal bankruptcies.

Medical debt is not a “budgeting problem.” It’s a structural trap—one that can hit insured, working, middle-class households just as hard as anyone else.

And the scale is no longer debatable: Americans owe at least $220 billion in medical debt. About 20 million adults (nearly 1 in 12) carry medical debt, including roughly 14 million who owe more than $1,000, and about 3 million who owe more than $10,000.

The Bankruptcy Link: Big, Real… and Easy to Mis-measure

You’ll often see a single headline number—“medical debt causes ~X% of bankruptcies.” Those figures typically come from surveys asking filers whether medical bills or illness contributed to their bankruptcy.

That matters, because health-related financial collapse isn’t just a hospital invoice. It’s usually a two-part shock:

-

The expense shock: deductibles, coinsurance, out-of-network charges, and repeat billing errors.

-

The income shock: missed work, reduced hours, disability, caregiving, job loss.

Some researchers argue the biggest “medical bankruptcy” claims can be overstated depending on the definition, and they caution against turning a complex chain of causes into a single percentage.

But here’s the point that survives every methodology fight: medical events reliably produce severe financial distress and often push already-tight households into insolvency. Bankruptcy may be the last step—after savings are drained, credit is maxed, and collections begin.

The “Insured Trap”: Coverage Isn’t the Same as Protection

The old narrative—“this only happens to the uninsured”—doesn’t match modern reality.

-

Nearly one in four adults ages 18–64 are underinsured: covered on paper, exposed in practice through high out-of-pocket costs and deductibles.

-

In 2025, the average annual premium for employer family coverage is about $26,993, with workers paying around $6,850 out of pocket just for the premium—before they even use care.

-

On top of that, the average single deductible in employer plans (among plans with a deductible) is about $1,787. And family deductibles in many plan types commonly sit in the $3,000–$5,000 range.

This is how you end up with “good insurance” and a five-figure balance anyway: premiums to keep coverage, then deductibles to access it, then coinsurance to finish the job.

The Hidden Engine of Debt: Denials, Confusion, and “Ghost Networks”

Medical debt often isn’t born from one catastrophic bill. It’s born from friction—the system repeatedly failing people in small but expensive ways.

Denials are a major accelerant. In ACA Marketplace plans, insurers denied about 19% of in-network claims and 37% of out-of-network claims in 2023 (roughly 20% overall).

Then there’s the access illusion: “ghost networks”—provider directories packed with listings that are inaccurate, unreachable, or not actually accepting patients.

What that means in real life:

You try to stay in-network. The directory lies (or is outdated). You get care anyway—because you have to. And suddenly an “in-network plan” becomes an out-of-network bill with none of the financial guardrails people assume exist.

The Credit Report Paradox: Relief, Then Whiplash

For years, medical collections were a major credit-score landmine. Medical collections tradelines appeared on tens of millions of credit reports, and medical bills made up a large share of collections on credit records.

There was a push to remove medical debt from credit reports more broadly—but the policy story turned messy.

-

A rule finalized in January 2025 aimed to keep medical debt off consumer credit reports.

-

In July 2025, a federal judge vacated that rule.

So if families believed “medical debt won’t affect credit anymore,” that can be a dangerous assumption. Some medical debt may be excluded in certain circumstances, but credit relief is not the same as debt relief—and it can change with courts and regulations.

When Credit Pressure Drops, Lawsuits Become the Weapon of Choice

Even when medical debt isn’t devastating someone’s credit, it can still be collected—often aggressively.

Provider collection policies vary widely. Many hospitals allow at least one “extraordinary collection action,” such as wage garnishment, selling debt, or denying non-emergency care for unpaid balances.

And the lawsuit pathway isn’t theoretical. A major study of physician-driven medical debt lawsuits in one metro area found nearly 1,000 lawsuits (Jan 2020–May 2023) from two large physician groups, with disproportionate harms in lower-income communities—often ending in judgments and wage garnishments.

That’s the real pipeline:

bill → dispute/denial → collections → lawsuit → judgment → wage garnishment → bankruptcy becomes “protection,” not “failure.”

Who Gets Hit Hardest

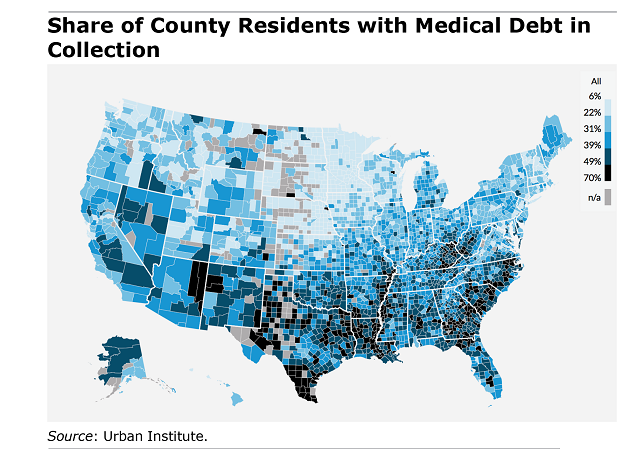

Medical debt isn’t evenly distributed.

The “working years” squeeze (18–64): Underinsurance is concentrated here, and this group is most exposed to job-linked coverage volatility and high cost-sharing.

Families living paycheck-to-paycheck: Even a “moderate” balance becomes lethal when savings are thin and rent, food, and car payments don’t pause.

People who try to do everything right: The insured who stayed in-network (until the directory was wrong). The patient who assumed the claim would be paid (until it wasn’t). The parent who thought the bill was inaccurate but couldn’t get answers fast enough.

What People Actually Do to Survive

This is where the crisis stops being abstract.

Among households with medical debt:

-

63% cut spending on basics like food and clothing.

-

48% use up most or all of their savings.

And increasingly, they borrow:

-

12% of U.S. adults—about 31 million people—report borrowing money to pay for healthcare, totaling an estimated $74 billion in a year.

That isn’t “irresponsible.” That’s triage.

The Bottom Line

Medical debt is unique because it’s not optional. You can postpone a vacation. You can downgrade a car. You cannot “opt out” of a stroke, a cancer diagnosis, a complicated pregnancy, or a child’s emergency surgery.

Until wages, plan design, provider access, and billing enforcement stop shifting costs onto households, the U.S. will keep running the same grim system:

health event → financial event → legal event → bankruptcy as the final insurance policy.