Trusted by some of the largest LTC providers in the country, covering over 200 senior care locations. We balance aggressive financial recovery with the compassionate care your reputation demands. HIPAA compliant.

Why Senior Care Centers Choose Nexa:

-

DSO Reduction: Our clients typically see a 10-15 day reduction in Days Sales Outstanding (DSO) within the first 90 days of partnership.

-

Applied Income Experts: We specialize in recovering “Patient Liability” funds that families often misappropriate while waiting for Medicaid approval.

-

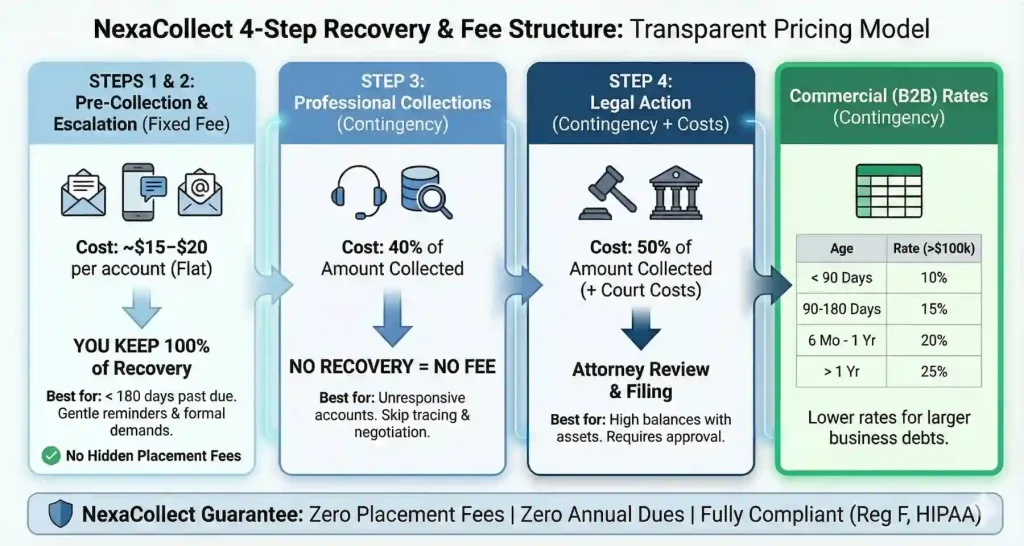

Zero-Risk Model: We operate primarily on a contingency basis—if we don’t collect, you don’t pay.

Managing the revenue cycle in a Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) or Long-Term Care (LTC) setting is uniquely complex. Unlike standard medical debt, you are dealing with Private Pay balances, Patient Liability (PL) amounts, and the sensitive nature of Estate claims. Nexa Collections understands this regulatory minefield. We recover the funds you are owed without violating resident dignity or federal statutes.

When Prevention Fails: Our Recovery Solutions

While internal financial counseling is vital, bad debt is inevitable. When families “ghost” you or assets are tied up in probate, we step in.

1. Private Pay & Patient Liability Recovery

The most common loss for SNFs is the “Patient Liability” (PL) or “Applied Income” portion that Medicaid does not cover. Families often treat this as their own money. We specialize in educating responsible parties on their legal obligation to remit these funds to the facility, recovering monthly co-pays that internal teams write off.

2. Probate & Estate Collections

When a resident passes away, collecting the final balance is uncomfortable for your staff but essential for your books. We handle the delicate process of filing claims against the estate, ensuring your facility is paid before assets are distributed to heirs. We do this with compassion and strict legal compliance.

3. Fixed Fee vs. Contingency Options

-

Fixed-Fee (Pre-Collect): Perfect for recent small balances (e.g., unpaid incidental fees or bed-hold charges). You pay a low flat fee per account, and you keep 100% of the recovery.

-

Contingency (Standard): For aged debt or estate claims. We advance all costs for skip-tracing and legal review. No Recovery, No Fee.

Need a Collection Agency? Contact UsServing Nursing Homes Nationwide |

The “Medicaid Pending” Trap

“Medicaid Pending” is a dangerous status. If a resident is denied Medicaid after 6 months of care, you are left with a massive private pay balance that the family often cannot pay. Nexa Collections helps you identify these risks early. We can assist in recovering funds where families have failed to provide necessary documentation to the state, effectively coaching them into compliance to get your retro-pay released.

The “$50,000 Failure”: Why Admissions Matter

In our experience, a $50,000 bad debt account usually starts as a $500 mistake at admission. The majority of uncollectible debt in nursing homes stems from incomplete financial intake.

Our Consulting Insight:

To maximize recoverability, your Admissions team must gather:

-

Copies of all Insurance/Medicare cards (front and back).

-

Social Security and Bank Statements (crucial for Medicaid applications).

-

Signed Responsible Party Guarantees: Ensure the contract explicitly holds the signer liable for handling the resident’s assets/income, not just the resident themselves.

Legal Compliance: The 1987 Reform Act

We adhere strictly to the Nursing Home Reform Act of 1987 and the FDCPA. We understand that you cannot simply “evict” a resident for non-payment without following complex discharge procedures. Our collection efforts focus on the financial guarantors and assets, ensuring your facility stays compliant with state survey requirements.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can we sue a resident’s children for the debt?

A: Generally, no—unless they voluntarily signed as a “Guarantor” or “Responsible Party” and mishandled the resident’s assets (e.g., taking Mom’s Social Security check). We review your admission contracts to determine exactly who is legally liable.

Q: How do you handle reputation management?

A: We know that a single negative review from an angry family member can hurt your census. Our collectors are trained in “Elder Care Sensitivity.” We act as firm problem solvers, not aggressors.

Q: Do you serve multi-state chains?

A: Yes. We currently serve over 200 locations nationwide, providing centralized reporting for corporate offices while handling local collections for individual facilities.

Protect Your Census & Your Cash Flow

Don’t let uncollected Private Pay balances limit your ability to provide quality care. Partner with the agency that understands the Senior Care industry.